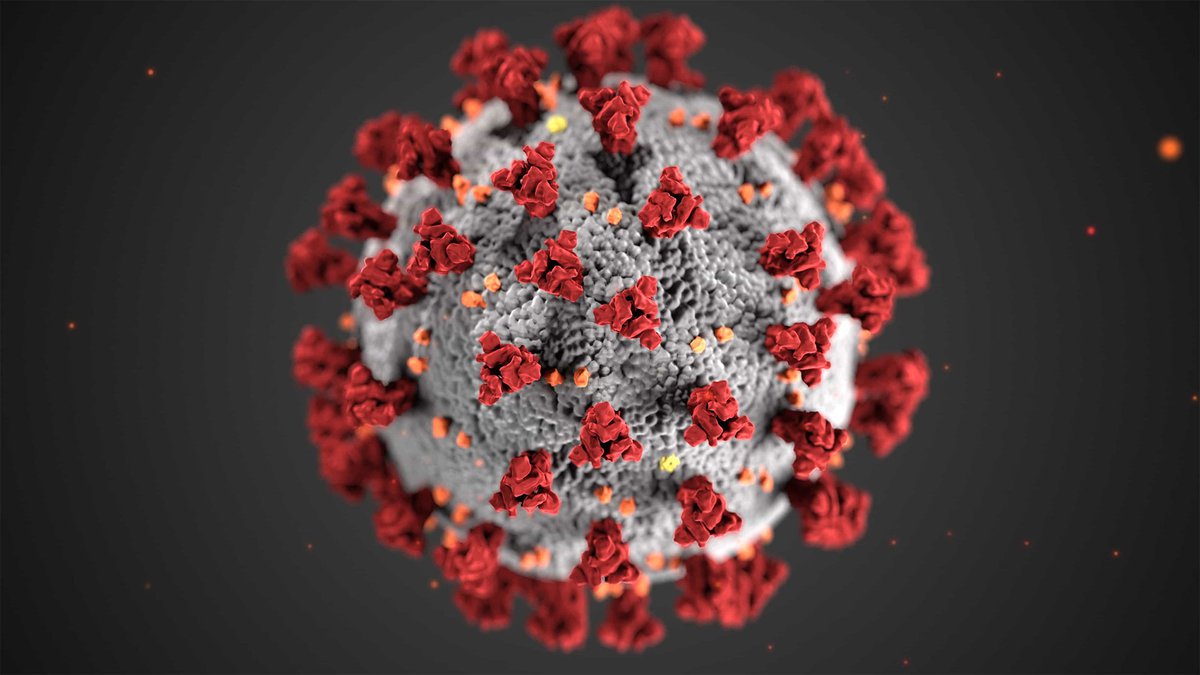

The coronaviruses are a group of RNA viruses that are characterised by the crown-like spikes on their surfaces. SARS-CoV-2 is the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic; it uses its surface spike proteins to bind to ACE2 receptors present in host/human cells to cause infections. There have been a few cases of different variants of SARS-CoV-2 following the pandemic, each bringing about new nuances to its viral mechanism.

Viruses mutate at a significantly higher rate than their host cells- leading to slight changes in their spike protein. While these changes are often disadvantageous or neutral, a few may provide increased chances of survival to the virus. Thus, they persist in nature. These changed viruses are genetically dissimilar to the main strain, but are not divergent enough to be a separate strain. So, they are termed as “variants” of the original strain.

The UK variant or B.1.1.7 first emerged in the UK in December 2020 and is responsible for 88% of the cases in the UK as of February 2021. It has spread to 50 other countries and has mutated to give rise to more strains. The mutation N501Y in its spike protein causes it to be 50% more transmissible due to an increased affinity towards ACE2 receptors. This means the strain is more infectious compared to the original one. The World Health Organisation (WHO) enlisted this variant as a “variant of concern”.

B.1.351 or the South African variant is also a “variant of concern”. It has accumulated the N501Y and E484K mutations in its spike protein. This not only increases its transmissibility but allows it to evade neutralisation by antibodies in the host. First detected in October 2020 in South Africa, it is responsible for 61% of the cases in the country as of February 2021. It is also the direct cause for the second wave of COVID-19 cases in Bangladesh according to ICDDR,B.

The Brazilian variant or P.1 has the same mutations as the South African variant. As such, immunity due to natural infection or vaccination is less protective; studies in Brazil showed high incidence rates of this variant even in patients who have recovered from the disease. This “variant of concern” is directly responsible for the recent resurgence of cases in Manaus, Brazil accounting for infections in 76% of the population in January 2021.

By April 2021, India faced the world’s largest spike in cases. Many scientists suspect this may be due to the Indian variant. Also known as B.1.617, this variant has already been detected in 17 countries and is a relatively new variant. Research is underway to determine the specifics of the variant and its mechanisms. It has been termed as a “variant of interest” by the WHO and may have increased transmissibility and severity of disease.

The efficacy of vaccines against these variants is still being looked into. Multiple studies found that the vaccines provided slightly less immunisation against these variants. For example, the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine has an efficacy of 75% against the UK variant, and a much lower 22% against the South African variant causing only mild to moderate progression of the disease, without the need for hospitalisation. Further studies are being done to shed light on the effectiveness of the current vaccines against the newly emerging variants.

0 comments